Project overview

CLIENT:

Communities in Schools (CIS)

ROLE:

Consultant

WHAT I DID:

Helped a leading youth development organization develop a 5-year strategic plan and organizational structure to support ambitious growth goals. Led work around identifying high-potential innovations to enable transformative scale.

SKILLS & METHODS:

Strategy

Benchmarking

Organizational design

Interviews

Quantitative analysis

Qualitative analysis

Executive alignment

Implementation planning

Presentations

Challenge

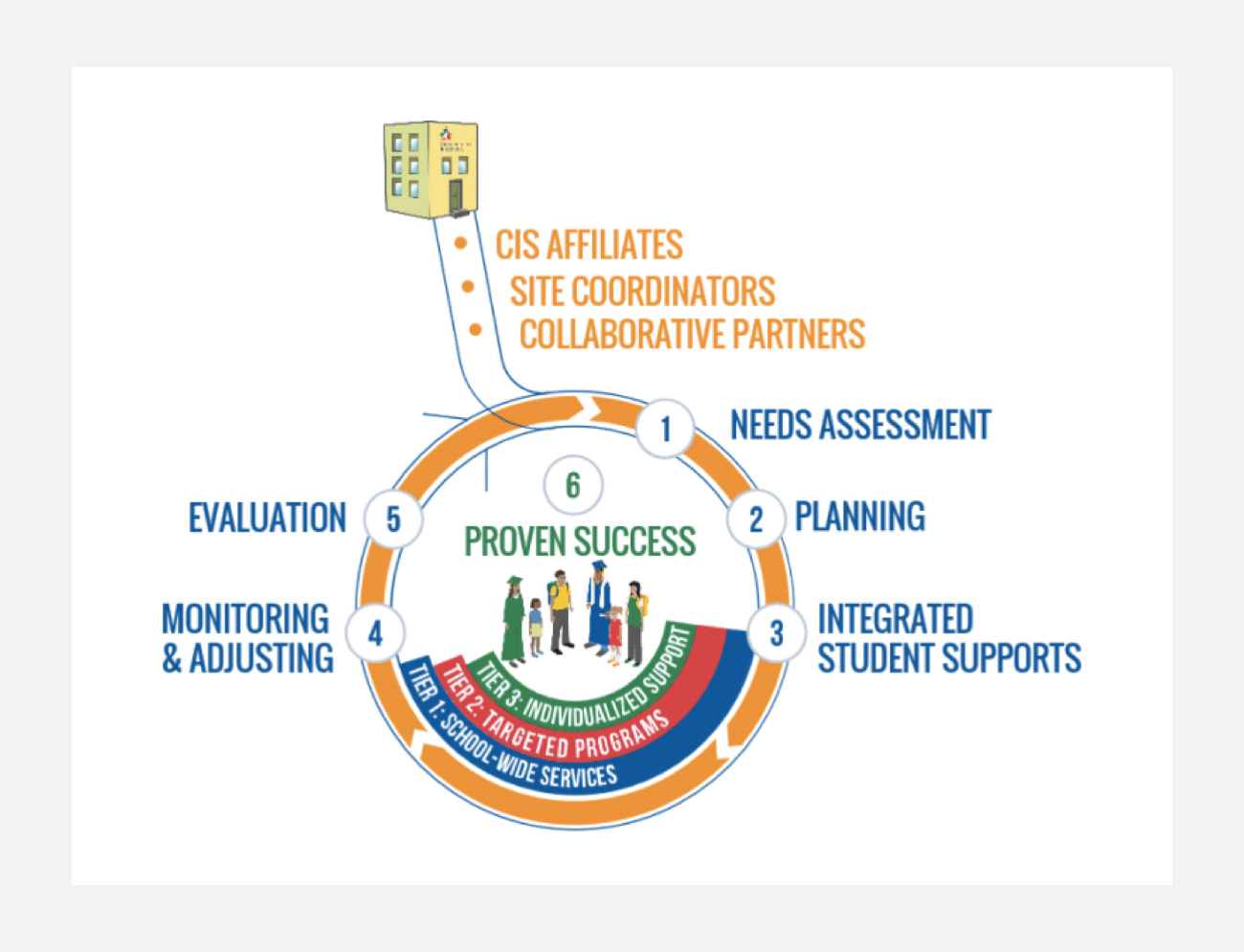

Communities In Schools (CIS) is a national organization working in public schools to surround students with a community of support, empowering them to stay in school and achieve in life. The organization improves access to public and community resources for struggling students by bringing those resources directly into schools. On-site CIS coordinators assess students’ needs, identify partners, monitor students’ progress, and connect families with a range of “integrated student supports” (ISS), thereby removing barriers for vulnerable students at risk of dropping out.

While CIS’s evidence-based model is widely recognized as one of the best in the country, with 91% of CIS seniors graduating or receiving a GED, the organization constantly strives to increase its impact. In 2014, CIS asked The Bridgespan Group, a nonprofit strategy consulting firm, to help the national network gain clarity on its next phase of growth. CIS sought to answer:

- How can CIS grow with quality to reach an additional 500,000 to 1 million youth?

- How can CIS build a stronger system of support for the estimated 11 million K-12 students living in poverty?

As a consultant at Bridgespan and someone with a strong interest in youth development, I eagerly joined the case team. It would not be a simple client engagement; the level of desired growth and complexity of the problem would require a new strategy and organizational structure. Undeterred, our team focused on helping CIS articulate its vision and define how best to invest its resources and unique capabilities to achieve its goals.

Defining project scope + ownership

Overview and roles

CIS is a massive national network. As of 2014, the group had a central office in Washington DC and a federation of 164 independent, non-profit affiliates. To create the right strategy for an organization of this size, our team identified four exploration areas, as related to CIS’s growth targets:

- How can CIS use “proof points” to build stronger demand for ISS?

- What innovations should CIS pursue in order to scale most effectively?

- In which priority geographies should CIS focus its growth investment?

- What approach should CIS take to help build a powerful coalition for reform?

We also identified a set of implementation questions we needed to address:

- What organization design, roles, and responsibilities does CIS national need?

- How should members of CIS’s leadership team allocate their time and energy?

- How much will the proposed initiatives and investments cost?

Given the collaborative nature of our five-person case team, I supported research and analysis across all areas. However, my main focus was on innovations that could help the organization scale effectively as well as reorganization needs at CIS national.

Project phases

The team mapped out a multi-phase approach. I organized my work as follows:

- Phase 1: Identify internal innovations

- Identify the most important, current innovations on CIS’s existing model that would help the organization support 500,000+ more youth.

- Phase 2: Identify high-potential, transformative innovations

- Identify large-scale innovations that could lead to a stronger system of support for the millions of students living in poverty.

- Phase 3: Redefine organizational design

- Develop a new network structure to support strategic goals.

Phase 1: Identify internal innovations

Overview

To identify potential pathways for growth and greater impact, I first looked to affiliates demonstrating strong results and creative operating practices. I hoped to surface existing innovations that could lead to increased scale, enhanced operating efficiency, and greater financial sustainability – outcomes that would support CIS’s ambitious goals.

Criteria for sourcing innovations

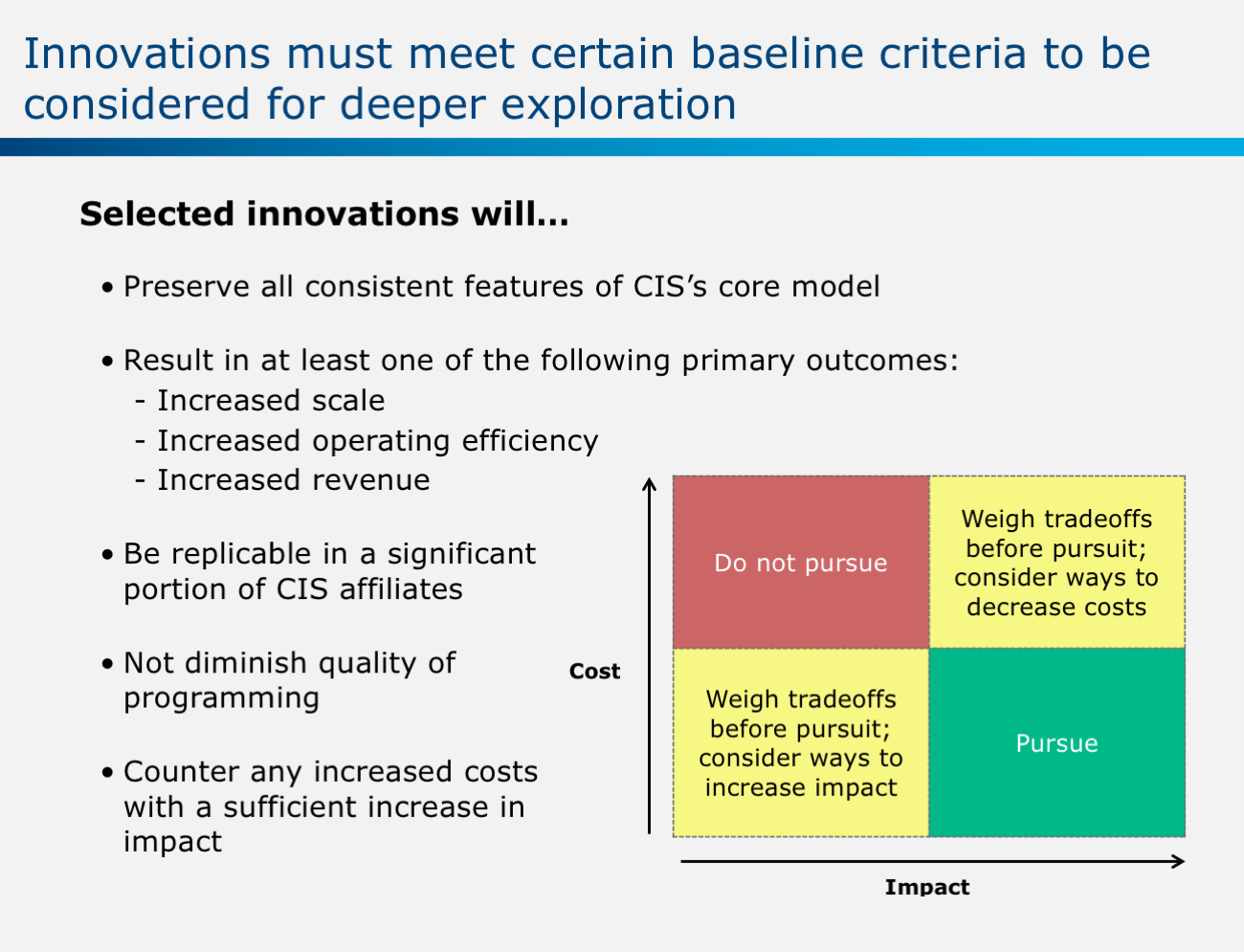

I worked closely with CIS’s executive team to identify promising affiliates. We started by defining our criteria for what would constitute the “right type” of innovation:

- Preserves all features of CIS’s core programming model (e.g., dedicated site coordinator, rigorous data collection)

- Results in increased scale, operating efficiency, and/or revenue

- Can be replicated in other CIS affiliates

- Does not diminish the quality of programming

- Counters any increased costs with a significant increase in impact

To identify the best candidates, I interviewed the CFO and VP of the National Network for quick thoughts on obvious innovators; scanned CIS’s model accreditation data for outliers, searching for groups that saw positive results from unique implementation strategies; and posted on the organization’s internal message board to gather information across the network and locate under-the-radar innovations. This search process yielded 35 candidates, and after applying the criteria, I was left with a final list of 14 affiliates.

Interviews

I conducted hour-long interviews with leaders of each of the 14 affiliates to understand how these variations came into being, what made them successful, what resources or contextual factors were required for implementation, and how feasible it would be to scale them more broadly. I developed an interview guide to ensure that comparable data came out of each interview.

Findings

I analyzed the data from the interviews, looking for themes, standout practices, and common success factors. In general, most of the innovations seemed worth sharing to stimulate creativity and inspire new thinking across the network. However, my analysis revealed that many of these efforts did not actually meet our initial criteria. For example, rather than increasing reach, the innovations often increased the intensity of services for the students they were already serving (e.g., providing a higher staff-to-student ratio). In other cases, rather than reducing the cost of the model, innovations enabled affiliate leaders to tap into new funding sources.

However, I did find several innovations that worked for our needs. In one case, multiple affiliates had joined forces to obtain economies of scale. Rather than serve one location, these joint affiliates covered multiple states as a single 501(c)3. The interviewee noted that, typically, CIS slowly established community partnerships over many years before delivering services. “But that’s a 35 year-old model,” she said. “It doesn’t work anymore. It’s pre-email, pre-PC. It’s too unwieldy. In our particular economic and geographic environment, that would not be successful.” The joint-affiliate model, on the other hand, reduced timelines and costs associated with launching new affiliates, improved the quality of partnerships thanks to skilled and experienced staff at a central office, and reduced costs by eliminating a layer of overhead associated with operating independent organizations.

In another case, two affiliates expanded their reach by placing site coordinators in non-traditional settings, including community colleges, Boys & Girls Clubs, community-based organizations, and charter schools. These affiliates maintained fidelity to the core model by keeping coordinators in public schools, while still adding others to these remote locations.

Another affiliate lowered costs by leveraging district and state employees as site coordinators. While the affiliate provided training, monitoring, and tools, the district and state agencies were responsible for day-to-day supervision.

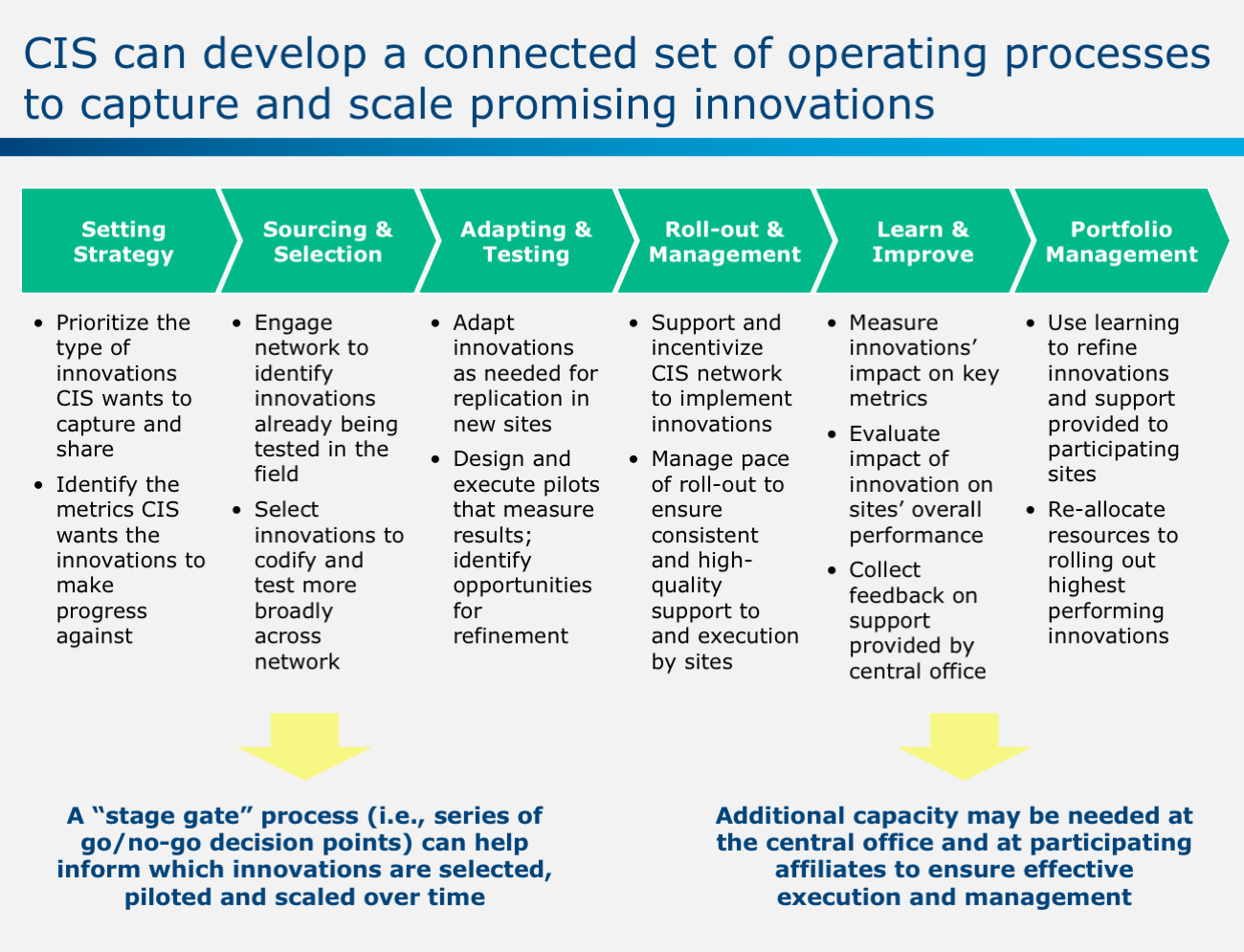

Given the success of these unique models, I recommended that CIS develop pilot sites to test these innovations further and track impact.

Phase 2: Identify transformative innovations

Overview

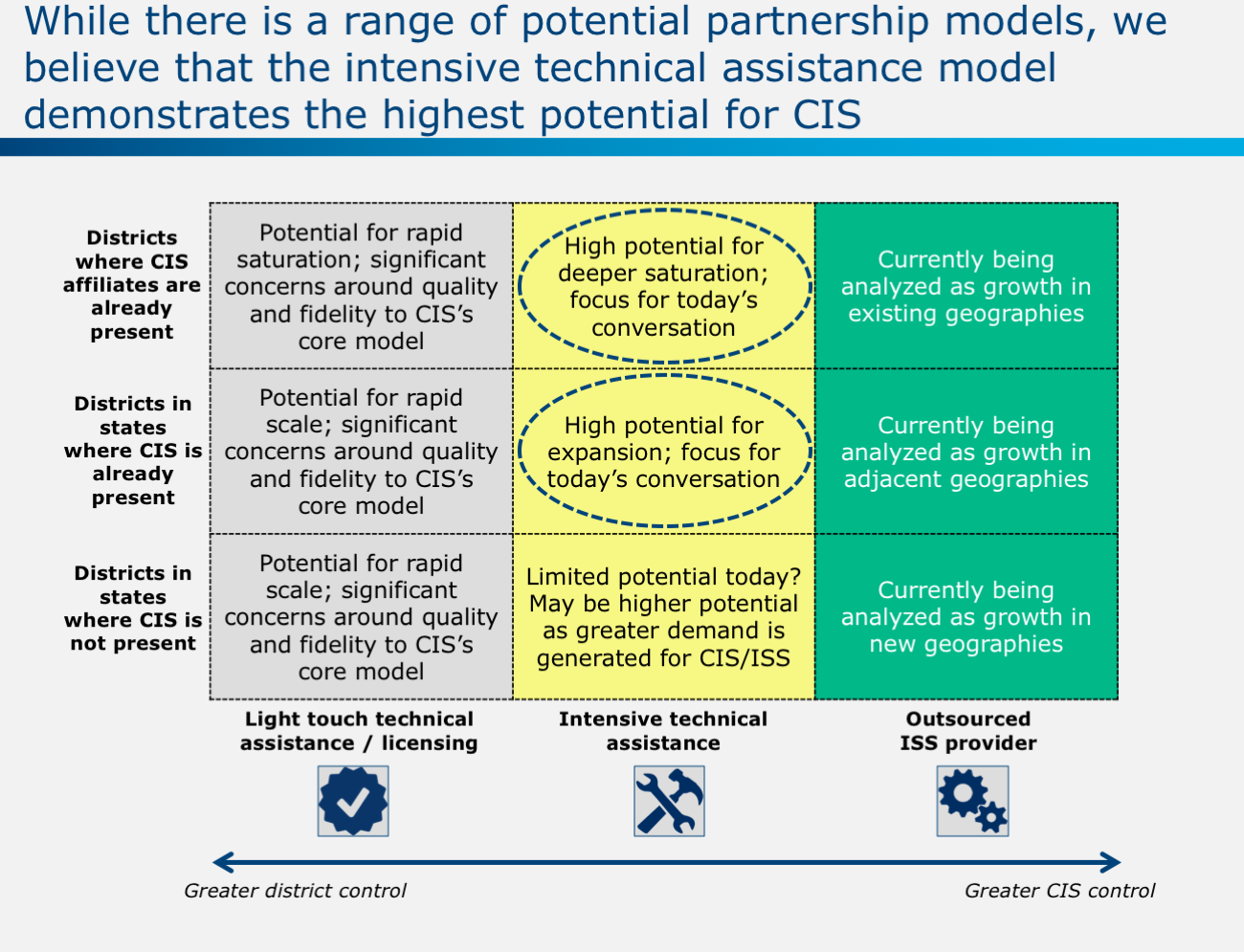

Next, I turned to CIS’s bigger goal of building a stronger system of support for all of the 11 million K-12 students living in poverty. I aimed to identify high-potential concepts for dramatically reducing the cost, reach, and/or impact of delivery of ISS. I built my approach around Bridgespan’s research on transformative scale, which outlines nine strategies for addressing difficult social problems via major systems change. I saw the most promise in developing new types of partnerships with districts, national nonprofits, and charter schools. I identified three high-potential pathways to explore:

- CIS as primary ISS provider: CIS would develop a formalized relationship with school districts or charter management organizations. In this case, CIS would be the sole provider of integrated student supports in all schools.

- CIS as technical assistance (TA) provider: CIS would package its model as a product for districts and charter schools interested in expanding services to provide ISS. CIS would offer technical assistance, training, and resources, but would not implement the model itself.

- Distribute through nonprofit networks: CIS would package its model as a product for large community-based organizations (CBOs) with extensive networks (e.g. YMCA or Boys & Girls Clubs). CIS would then work directly with CBOs to offer these services outside of a school setting.

After conversations with districts, charter schools, and CBOs to assess interest, fit, and funding, I identified school districts as the highest potential partner. Given this, I focused my research on the first two pathways that I identified.

District partnerships

In partnering with districts, CIS had potential to scale up and have a broad, systemic impact on integrated student support. Since many districts already invest in ISS, CIS would be well-positioned to help them do this with greater quality, stronger outcomes, and lower cost.

What’s more, as a partner, districts would provide CIS with a range of unique benefits:

- A single access point to a vast number of students.

- The ability to implement and sustain ISS across high-need schools in an integrated, prioritized way.

- This could lead to quicker Title I saturation, stable funding for ISS, and long-term support for students on their journey to high school graduation.

- The power to influence others and advocate for CIS’s model on a broader policy stage.

In order to assess the viability of this concept, I looked closer at how CIS might structure such a partnership.

Option 1: Primary ISS provider

As the primary ISS provider within a district, CIS employees would deliver all relevant services across K-12 sites. This would involve building ISS into a district-level strategy so that all students who needed CIS’s services, particularly those in Title I schools, would have access. In order to preserve CIS’s brand integrity and evidence-based approach, CIS would not only need to secure partial or full funding from district partners, but would also need to maintain or improve the quality of their current services.

To assess this option, I interviewed districts, conducted focus groups with education experts, and analyzed budgets to understand related costs and spending patterns. While districts showed high interest, they worried that it would be difficult to secure funding for such a large-scale roll out, and that hiring CIS would create tensions with existing staff and union members. One district interviewee noted, “I would want more district and school control and involvement. Principals always have someone in mind that they want to be doing school supports. A lot of the time, those people are already in the system, on our payroll. We’d want to use those people, and then outsource training.”

Education experts expressed concerns about CIS’s capacity to implement a model effectively across an entire school district and stressed that it would take time to develop partnerships with social services providers and prepare to launch operations in multiple schools simultaneously. One program officer from a leading education philanthropy warned, “Unless CIS has existing relationships in the area, it can take months [or even] years to gain credibility in a community.” One way to mitigate this would be to roll out more slowly, yet that would undercut CIS’s goal of immediate, transformative scale and could increase cost.

For CIS to succeed as the primary ISS provider within districts, it would need to find the right partners, taking into consideration size, resources, and interest in implementing a new model. This would be a challenge.

Option 2: Technical assistance provider

As a technical assistance (TA) provider, CIS would package its model as a product for districts, providing training and evaluation support to help districts improve their ability to offer high-quality integrated student supports. Districts would then be responsible for implementing the model where needed, using district employees as site coordinators.

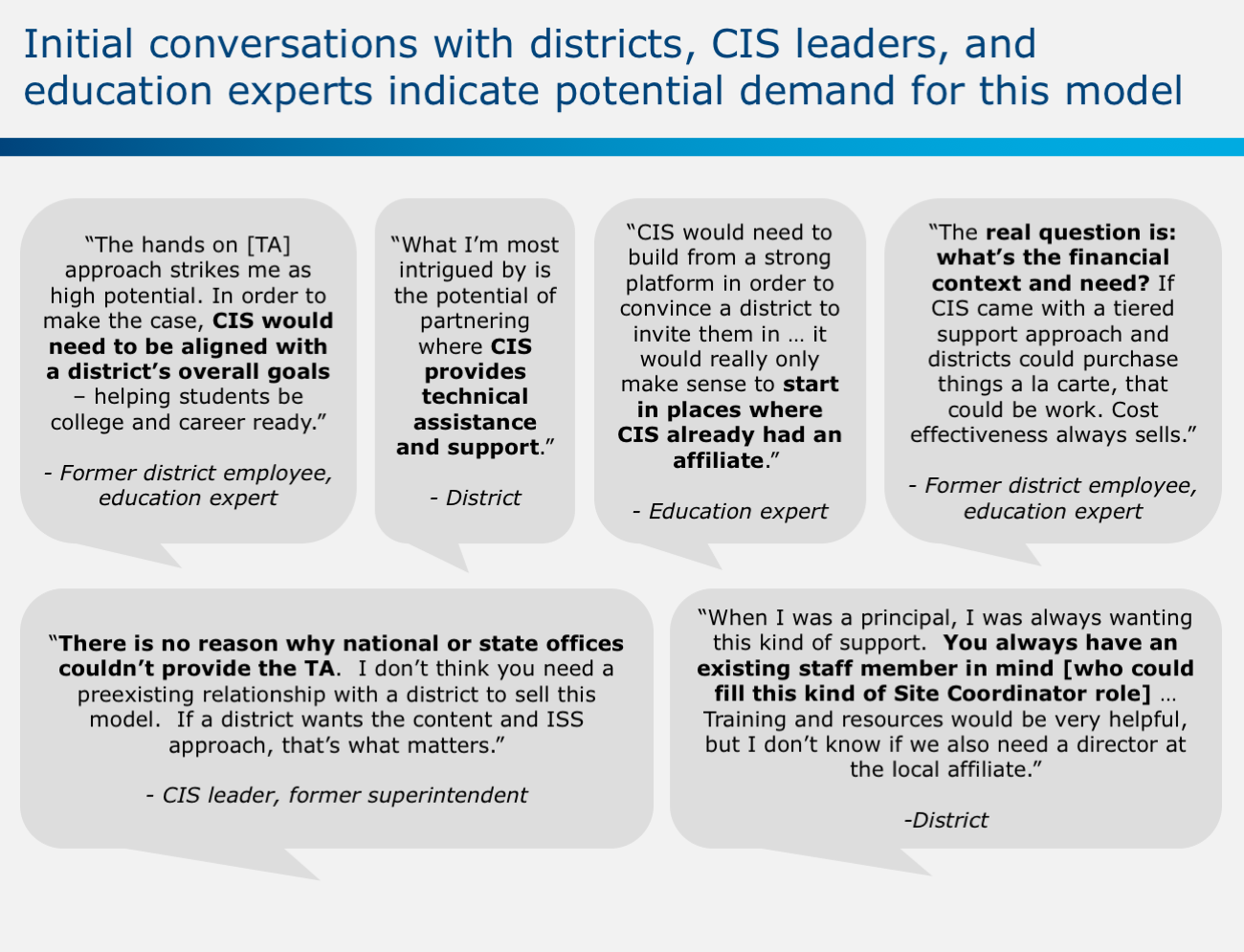

I conducted research and interviews with districts, education experts, and CIS affiliates. I asked each of these stakeholders about how they viewed the benefits and risks. In particular, I asked about the possibility of using district staff as site coordinators, concerns around model fidelity, the role that CIS affiliates versus CIS’s national team might play in providing training, and funding.

Through these conversations, it became clear that districts wanted a smarter approach for delivering ISS and that the TA model seemed aligned with their needs. Whereas the “primary ISS provider” approach raised red flags about resources, the TA model would enable districts to reposition existing staff to fill the site coordinator positions. What’s more, several CIS affiliates had already implemented versions of this model with success, giving the organization a jumpstart on future pilots.

Findings and recommendations

While CIS would need to think carefully about potential risks, the TA approach showed real promise for transformative scale. The model offered clear benefits to both districts and CIS, enabling the organization to expand its reach and enhance its field-building efforts.

Benefits for districts

- Offers an evidence-based model with proven outcomes

- Improves districts’ ability to own and deliver effective ISS over time

- Offers higher quality training, support, and data collection systems through CIS’s established infrastructure

- Repositioning district employees reduces the incremental cost of the model

- Brings additional resources to the schools via services, supplies, and assemblies paid for by CIS

Benefits for CIS

- Enables CIS to expand reach quickly by building on existing infrastructure

- Lowers staffing cost to CIS

- Increases menu of offerings and makes CIS more appealing to wider range of districts

- Does not require new operating structure

- Supports long-term systemic change through district champions

- Leverages the work of strong affiliates to develop tools, training materials, and supports that benefit districts as well as the broader network of affiliates

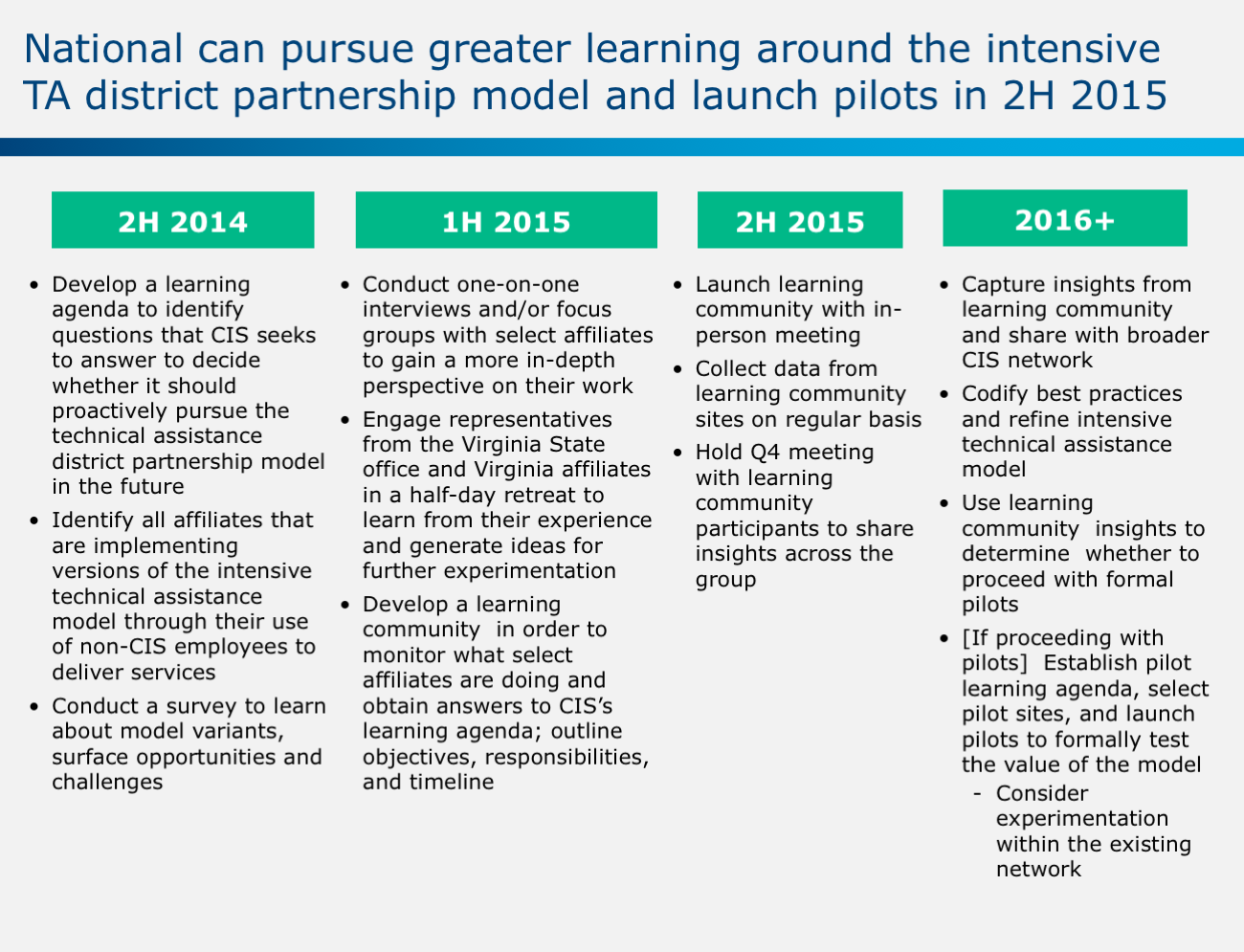

Piloting this approach would require resources and support from CIS national. However, I argued that CIS could first make some minimal, near-term investments, such as developing a learning agenda and gathering insights from affiliates already experimenting with district partnerships, to decide whether to move forward with this strategy.

Phase 3: Redefine organizational design

Overview

In order to achieve its major strategic goals, CIS would need to evolve as an organization, adding new capabilities and capacity. Structural shifts would also help CIS provide intensive support to affiliates, focus attention on field-building, and pursue innovative pathways to impact. For the final phase of this project, I helped CIS redefine its organizational structure to support growth in a thoughtful way.

Interviews with members of the leadership team surfaced three primary design goals to guide my work: 1) Greater support for affiliates and externally facing functions, 2) Greater clarity on new expertise and capabilities needed, and 3) More linkages across functions.

Research and benchmarks

After speaking with members of the executive team to get a better understanding of current needs, I conducted interviews and benchmarking research on similar organizations to compare structural models. My research revealed that, while there is no one solution for how best to organize network support, there are several best practices to consider. These include segmentation strategies, the provision of differential levels of support, and using “points of contact” to coordinate services.

I also noted that structures tend to have two components: groups and links of activities. “Groups” are how individuals, jobs, functions, and activities are divided within an organization; “links” are how these different groups connect with one another. An optimal organization structure has a balance of both differentiation and integration.

Proposed model

Based on this research and taking into account CIS’s vision for the future, I proposed that the organization consider a differential support structure with three affiliate segments: demonstration sites, new priority geographies, and the remaining network. Depending on its needs, each segment would receive some mixture of baseline, individualized, and expert support services. This revised support structure would require CIS national to invest in additional staff, including new functional experts in fundraising, policy and advocacy, finance, marketing and communications. Support for groups would be coordinated through points of contact, who would regularly assess strengths and challenges as well as field support requests.

This model would encourage deeper understanding of the affiliate experience and increase a sense of shared accountability for the strength of the network at large. In order to establish this new culture, CIS would need to raise funds to support investments in specific affiliates, hire and onboard needed staff, develop a change management plan focused on the successful adoption of the new structure, and align national staff around shared responsibility for the network.

Implementation + impact

To support CIS in making structural changes and executing its larger vision, our team developed a 5-year strategic implementation plan. This plan laid out the goals for each initiative, including CIS’s innovation agenda, and defined the timeline, actions, and costs required for success. We provided CIS with a fully fleshed-out network support structure, newly defined roles and responsibilities for the team, and a transition plan.

Armed with these guiding documents, CIS began to implement changes. Just one year later, CIS was already serving 15% more students. The organization was beginning to make progress.